Microbes in the school lab: Close encounters of the third kind !

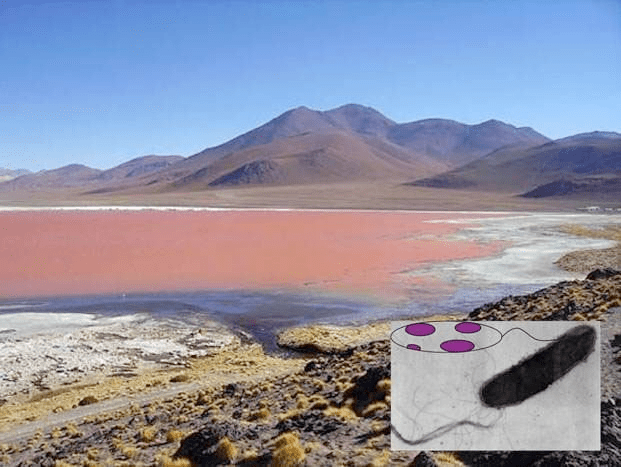

Halobacterium salinarum blooming in a salt lake (red color)1

The teaching of microbiology may be problematic if its practical aspects cannot be performed in sterile environments. Most of the schools do not have a dedicated microbiology lab and the handling of microorganisms is usually done in a biology or a chemistry lab which lacks any controlled environment. This situation makes contaminations almost unavoidable and practical microbiology activities are very limited.

In addition, any microbiology laboratory should be classified according to biosafety regulations (Directive 2000/54/EC). When applied to basic school labs, teachers and students are supposed to work with biological agents that are non-pathogenetic, implying that no specific biocontrol is required. Nevertheless, the principles of good occupational safety and hygiene should of course be observed.

In the search to find a solution to these issues, Prof. S. DasSarma from the University of Maryland, USA, and his colleagues have pioneered the use of Halobacterium salinarum (H. s.) as a model organism in classrooms2. The advantages of working with this microorganism are:

- Like all presently known Archaea, it is not pathogenic.

- Due to its extremely halophilic (salt-loving) living conditions, the handling of H. s. doesn’t require sterile conditions (e.g. autoclaving media, sterilizing utensils, etc.). A clean working place and the observance of good hygienic practices are sufficient for working with this microorganism.

Moreover, I have paid special attention to use, to the extent possible, daily life labware and chemicals. For example, laboratory utensils were recycled kitchenware (plastic or glass), chemicals were supermarket products and basic devices (heaters, lamps, etc.) were domestic electric appliances. The aim is two-fold:

- to make experimental costs as low as possible in order to make science more accessible and

- to reduce the waste generated by scientific activity.

Since its first description in 1922, the peculiar biology of H. s. has been extensively documented. The purpose of this article is to show that microbiology can be made simple while discovering new concepts in biology.

What is Halobacterium salinarum?

Unlike its name suggests, H. s. is not a bacterium, it is a rod-shaped microorganism (2-6 µ length, 0.4-0.7 µ diameter) belonging to the Archaean domain of living beings3.

“Haloarchaea” (salt-loving Archaea) are among the most ancient lifeforms and appeared on Earth billions of years ago.

H. s. is an extremely halophilic microorganism. It grows in very high saline environments in which the concentration of sodium chloride (NaCl) may go up to 5 mol.L-1 (290 g.L-1) which is close to saturation: at 20°C, the solubility of NaCl is 358.5 g.L-1. H. s. is found in high salt food (e.g. “Bacalau” salt-preserved cod), hyper-saline lakes, and salterns. Due to their high salinity, these salterns develop a reddish or pink colour with the presence of halophilic Archaea and algae like Dunaliella. As a species that colonises salterns, H. s. is known for its distinct colour and abundance at places with saline levels are reaching 4 mol.L-1 NaCl.

H. s. is an obligate aerobe (needs oxygen to grow). However, when oxygen is depleted, as it happens in salterns where temperature and cell densities are high (around 107 – 108 cells.ml-1), the water gets a distinctive red colour. This is due, among other things, to the presence of bacteriorhodopsin, a photoactive enzyme providing an alternative energy for growth, in its cell membranes.

Activity 1: Culture and observation of H. s.

Enquire from your local school lab supplier if H. s. is available. Samples are usually delivered as colonies on a Petri dish. H. s. maybe easily subcultured several times.

Culture media formulations:

For school labs, I have been selecting a formula that is easy to prepare considering the use, when possible, of daily life ingredients and the growth performance on solid and liquid media.

In the present case, we will prepare a “basal medium”: a medium containing water, a carbon source, a nitrogen source and various mineral salts but with a very high NaCl content.

Basically, there are two types of media depending on their physical state: solid and liquid. This article will focus on solid media.

“Solid” means that the medium, initially prepared as an aqueous solution, is gelled by addition of agar-agar, a polysaccharide of algal origin, and subsequent heating and cooling. After being inoculated at the surface of the gelled medium, microorganisms develop and are visualised by the appearance of “colonies”.

In this activity, we will learn the basics of media formulation and show examples of colonies of H. s. developing on solid media.

Materials

Chemicals (or ingredients) are listed in the following table.

| Chemical/Ingredient | Chemical formula | Amount g.L-1 | Molarity (Mole.L-1) | Common/Brand name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium chloride | NaCl | 250 | 4.28 | Table salt |

| Magnesium sulfate heptahydrate | MgSO4.7H2O | 20 | 8.1*10-2 | Epsom salt |

| Trisodium citrate | Na3C6H5O7 | 3 | 1.2*10-2 | |

| Potassium chloride | KCl | 2 | 2.6*10-2 | |

| Yeast extract | 5 | Freeze dried beer yeast (debittered) | ||

| Peptone | 5 | Bovril® | ||

| Powdered agar | 20 | |||

| Water (deionized) | H2O | Up tp 1L |

Keeping in mind the availability of chemicals/ingredients, microbiological grade powdered yeast extract and peptone have been replaced by similar ingredients obtained from local stores. When solid media are considered, the clarity of the growth substrate is usually not an issue and yeast extract maybe replaced by dried/lyophilised yeast flakes and peptone by culinary meat extract. These two ingredients are easily available in supermarkets, as well as deionized water.

Powdered agar is more difficult to obtain from supermarkets but it can easily be found in drugstores or health food stores. However, this “diet” type of agar is less easy to dissolve than bacteriological grade agar.

Please note that NaCl (kitchen salt) and KCl (also available in supermarkets for low sodium diets) should be chosen pure, without any additives. Epsom salt is available in pharmacies. Na3citrate is a food additive (E331) and is used here as a pH buffer. Ideally, but not mandatory, the pH of this medium should be adjusted to 7.5 (slightly alkaline, like seawater).

- 1L graduated cylinder

- 1L beaker or similar glassware

- Scale (0.1 g accuracy)

- Spoons or spatulas for weighing

- 1L Erlenmeyer flask or similar glassware

- Magnetic stirrer with heating and magnetic rod

- A few plastic Petri dishes (Ø 88 mm is fine)

- Cotton buds

- A Halobacterium salinarum strain

- Optional: a handheld UV (black light) lamp

Procedure

- Completely dissolve the mineral salts in about 750 mL of hot deionized water in a glass container and pour the solution in the graduated cylinder. Allow to cool down to room temperature.

- Add yeast extract and peptone in the cylinder and adjust to 1 L with deionized water; mix well. Agar won’t dissolve at room temperature; it is recommended to add the agar when the medium is brought to a boil in the Erlenmeyer flask. Mix well while boiling to avoid clogging. Because of its very high salinity, it is not necessary to autoclave this medium !

- Let the medium cool to +/- 40°C and pour about 15-20 mL into the Petri dishes. Put back the lids on and allow the medium to gel at room temperature. If no experiment is performed afterwards, the Petri dishes maybe stored for several days in a refrigerator. It is preferred to store them upside down to avoid condensation.

- Collect H. s. samples from the original Petri dish by gently rubbing the pink coloured colonies with a cotton bud.

- Inoculate the surface of the freshly prepared Petri dishes, put the lid back on and let them incubate at room temperature (25°C) for at least 1 week.

Note

The ideal growth temperature is 37-40 °C. In these conditions, colonies grow much faster.

Observations

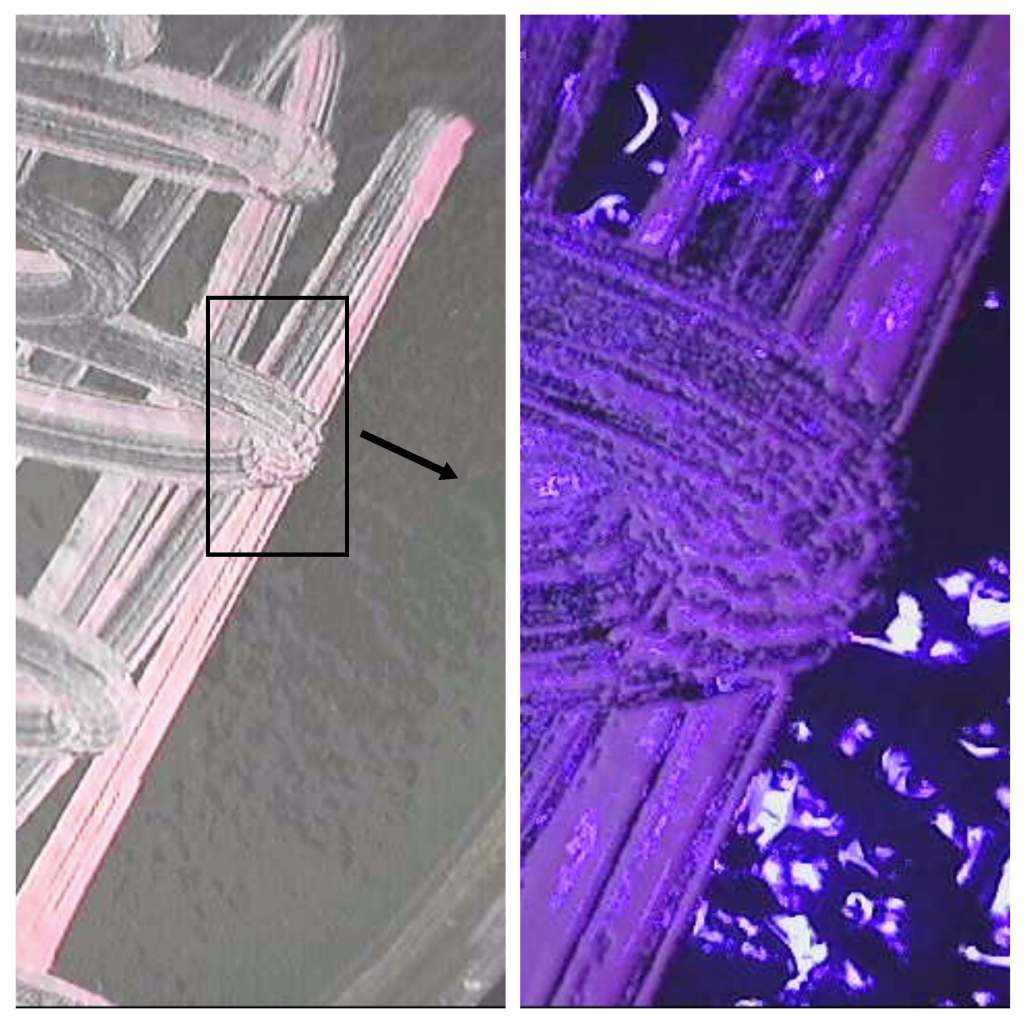

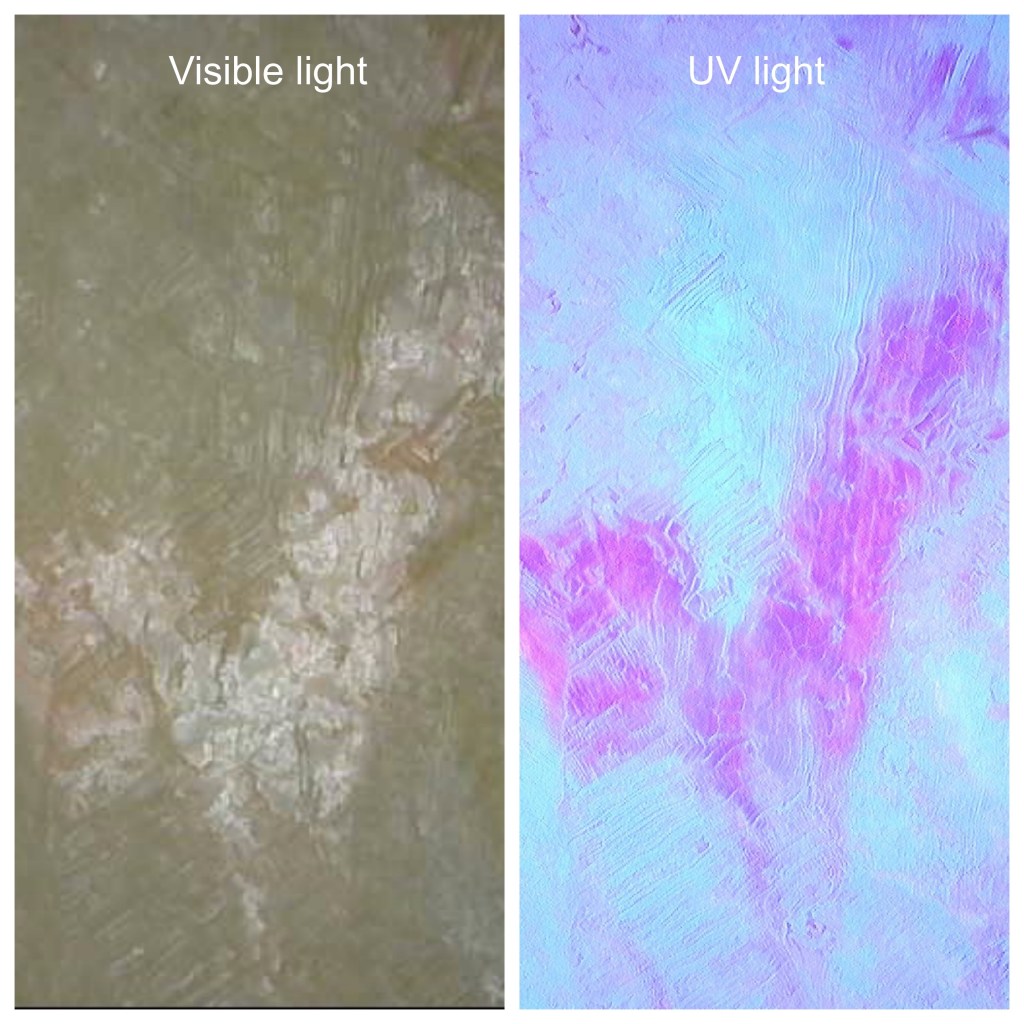

The appearance of colonies becomes detectable after 2-3 days of incubation. Well defined pink coloured microbial structures appear after about one week (Fig. 1). Under UV light the colonies brightly fluoresce in purple (Fig. 2). When the incubation time increases, salt crystals start precipitating inside the agar (Fig. 3) where microbial colonies become embedded.

If Petri dishes are left unattended for a long time, the whole culture dries out but, surprisingly, H. s. cells stay alive and can be subcultured. Fig. 4 shows a cluster of cells embedded in crystallized salt both under visible and UV light.

Discussion

In all respects, H. s. is unique and raises great interest. The following questions may initiate further documentary research with students:

- Maybe this was your first contact with microbiology. What did you learn?

- Microbes have lots of applications (food technology, medicine, ecology…). Do you think H. s. has specific applications?

- Why halophilic archaea are considered as one of the first lifeforms on Earth?

- What is fluorescence? Do you have an idea why H. s. cells fluoresce?

Activity 2: H. s. under the microscope

The best way to visualise individual cells is -of course- under the microscope. Here is a simple protocol describing this activity.

Materials

- NaCl 20% aqueous solution

- Acetic acid 2% aqueous solution or alcohol vinegar (6°/8° acidity) diluted 3/4-fold

- Crystal violet 0.25% aqueous solution for staining

- Distilled water

- Immersion oil (for microscopy)

- Plastic pipette

- Microscope

Procedure

- Pour a few mL of the NaCl solution in a Petri dish containing well developed colonies.

- With a cotton bud, remove the colonies by gently rubbing to obtain a cell suspension. This suspension shouldn’t be too thick. A slightly pink-coloured liquid is sufficient.

- 3. Drop a small drop of this microbial suspension on a microscope slide.

- Let this drop dry out, salt crystals will precipitate.

- Dip the slide in the acetic acid solution for 5 minutes, this step fixes the cells and dissolves the salt.

- Remove the slide from the acid bath and let it airdry.

- Put a drop of crystal violet on the preparation and let incubates for 3 minutes.

- Remove the stain by thoroughly washing with distilled water.

- Let the slide dry.

- Observe under the microscope without a cover slip at a 1,000x magnification with immersion oil.

Observations

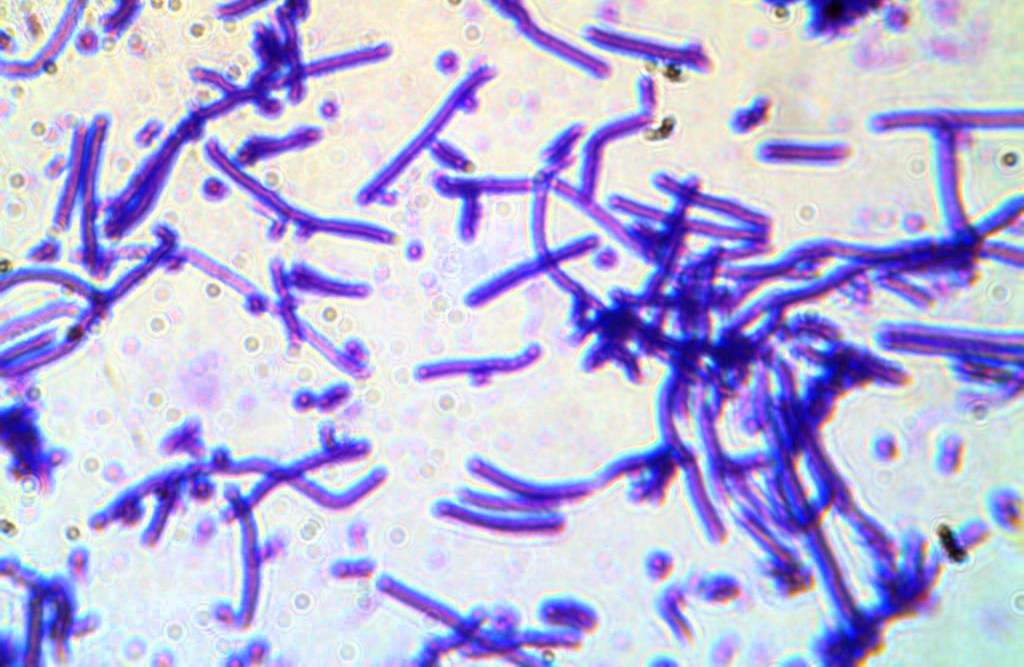

Cells are clearly visible and show a deep violet colour (Fig. 5). Cells are rod-shaped and appear flexible due to the absence of cell wall.

Discussion

- Why do you have to suspend H. s. cells in a 20% salt solution?

- Why is it necessary to stain the cells?

- Have you ever heard about the Gram stain? What is the difference with the present protocol?

- Who invented the first microscope?

Notes & References

- https://alchetron.com/Halobacterium-salinarum

- https://halo.umbc.edu/haloed/intro

- All living organisms are clustered in three « Domains » : Archaea, Bacteria and Eucarya. The lineages encompassing the total biodiversity are represented under a diagram called « The tree of life ». The most recent version of this document, based on data from molecular genetics and bioinformatics has been published. See: « A new view of the tree of life. » Nature Microbiology. Volume 1, Article number 16048 (2016).